When I was a child we had a black and white television, I guess that was all my parents could afford at the time. I even remember a time when we had no television.

My mum worked as a part time cleaner when I was young and I remember the marriage of Princess Anne to Captain Mark Phillips being televised. Apparently it took place on November 14th 1973 at Westminster Abbey.

One of the ladies Mum cleaned for, Mrs Bacon, lived in Friday Street, closer to the village than us and in an old Cotswold stone cottage. Even in her dotage Mrs Bacon liked to keep up with all the new ideas and she had a TV. I guess she must have invited my Mum to come and watch because I remember going there and trying to be dreadfully polite whilst the BBC broadcast the wedding. The living room was full of old fashioned chairs that were really uncomfortable and I was doing my best not to fidget.

Eventually television must have arrived at our house and my Dad took to watching the Western movies and so it was that Cowboys and Indians took over my younger years. I loved John Wayne in films such as Big Jake, Chisum and El Dorado, Clint Eastwood in a Fistful of Dollars and the emergence of his fellow actor Lee Van Cleef in For a Few Dollars More. Then there was Wayne alongside James Stewart in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence and of course film of films -The Magnificent Seven. I was only a child but these were the movies that influenced me into learning to ride when I was eight years old. I wanted to be one of those Indians tearing across the local common bareback on my horse.

That early introduction to how the west was won never left me throughout life and whenever a new film of that genre arrived at the cinema I would be there. The Oscar winning 1990 film “Dancing with Wolves” starring and directed by Kevin Costner still ranks in my Top Five ever movies and I couldn’t wait for the remake of The Magnificent Seven in 2016 to be released at cinemas.

And so to our current adventure driving Route 66 and our arrival in St Louis. This city sits on the border between Illinois and Missouri, across the Mississippi River, and this was where the exploration of the west all began. I couldn’t possibly travel through without going to the Museum of Western Expansion and this was where the real story of the Wild West came to light……………..

The museum tells us “that prior to the Louisiana Purchase, French merchant Pierre Laclede and Auguste Chouteau selected an ideal site to build a commercial village, which they named St. Louis. Near the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi, St. Louis became a hub for trade with regional American Indian tribes such as the Osage. French officials, Spanish administrators, and entrepreneurial citizens arrived and built the village into a significant trading post and the political capital of the region. St. Louis quickly became an affluent and cultured place due to its natural advantages and the people who came here to make their fortunes.”

Trading with the Indians became common place. Contrary to what the Western movies had fed me the animosity between the “pale faces” and their native counterpart did not exist at this time. In fact the term “I bought it for a buck stems from this era”!

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803, when the United States purchased 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million from France changed the course of history. For roughly 4 cents an acre, the United States doubled its size, expanding the nation westward.

Thomas Jefferson, the then President, knowing that the Spanish and English had mapped a lot of the Pacific Coast and Canada, realised that in order to gain supremacy in North America he needed to fund an expedition to map this country west of St Louis.

And so it was that in May 1804 Meriwether Lewis headed this critical mission and left St Louis with a crew of about fifty including his fellow comrade William Clark . They didn’t return until over two years later in September 1806.

They didn’t find the NorthWest passage that Jefferson craved because there was no water route across to the Pacific but they did provide overland travel to the Pacific. Furthermore their journals and sketchbooks were filled with incredible details of the western lands. Lewis mapped rivers, traced the principal waterways to the sea, and established the American claim to the territories of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

Today, the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia holds the journals kept by Captains Lewis and Clark. They consist of eighteen small notebooks, approximately 4×6 inches, of the type commonly used by surveyors in field work.

Amongst the crew Lewis and Meriwether took with them was a Native American woman called Sacagawea. Sacagawea was either 16 or 17 years old when she joined the Corps of Discovery. She met Lewis and Clark while she was living among the Mandan and Hidatsa in North Dakota, though she was a Lemhi Shoshone from Idaho.

She was instrumental in the Lewis and Clark Expedition as a guide as they explored the western lands of the United States.

Most of the land Lewis and Clark surveyed was already occupied by Native Americans. In fact, the Corps encountered around fifty different Native American tribes including the Shoshone, the Mandan, the Minitari, the Blackfeet, the Chinook and the Sioux.

The presence of Sacagawea, as a woman, helped dispel notions to the Native tribes that they were coming to conquer and confirmed the peacefulness of their mission.

The Journals of Lewis and Clark are readily available to those who wish to read them and I left the on site shop with my own copy to take back to the UK. These were the original explorers of Western America.

Moving on through the museum I was intrigued to find out when and how the settlers travelled west.

Again my Western movie viewing didn’t bear fruit because the first white Americans to move west following Lewis and Clark’s exploration were the mountain men, who went to the Rockies to hunt beaver, bear and elk in the 1820s and 1830s.

It wasn’t until 1841, that the first wagon train set out on what was to become the Oregon Trail to the north-west coast of America.

In the mid-1800s, many Americans believed the United States had a God-given right—a “manifest destiny”—to expand and so it was that between 1840 and 1860, from 300,000 to 400,000 travellers then went on to use the 2,000-mile overland route to reach Oregon, NW Washington, Utah, and California destinations. The journey took up to six months, with wagons making between ten and twenty miles per day of travel. The trail was arduous and snaked through Missouri and present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and finally into Oregon.

Contrary to the scenes from the Western movies these pioneers did not ride in the wagons drawn by horses. They generally walked 10 to 20 miles each day and the wagons were used to store their meagre belongings but more importantly their food supplies. A family of four needed nearly 2,000lbs of food supplies to sustain them along the trail.

It is estimated that as many as 1 in 10 emigrants died on the trail—between 20,000 and 30,000 people. The majority of deaths occurred because of diseases caused by poor sanitation. Cholera and typhoid fever were the biggest killers on the trail.

Indian attacks were relatively rare on the Oregon Trail. While pioneer trains did circle their wagons at night, it was mostly to keep their draft animals from wandering off, not to protect against an ambush.

Again books are available retelling the true stories of these pioneers, one of which is now waiting in my suitcase and my return home.

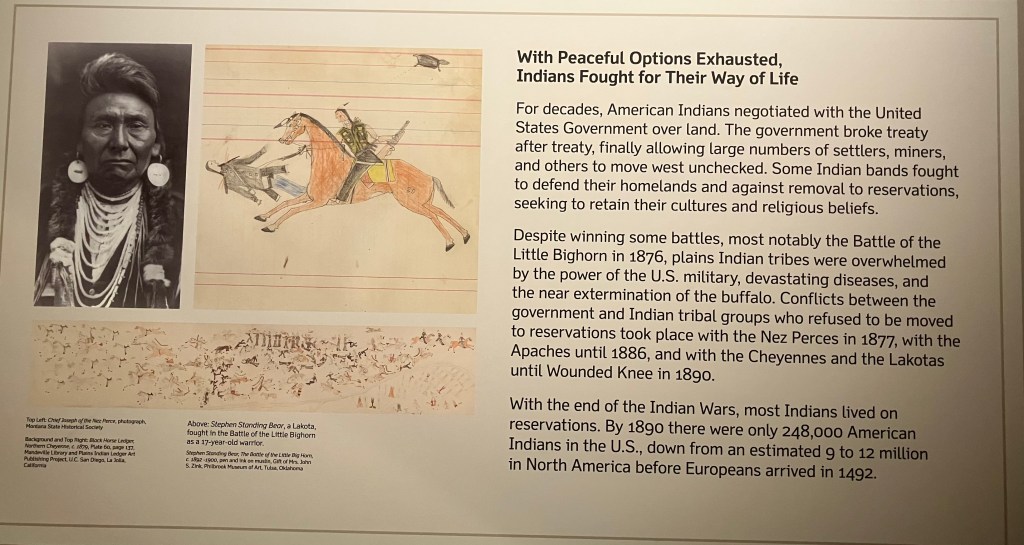

Alongside this emigration in 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which empowered the federal government to begin the forced relocation of thousands of Native Americans in what became known as the Trail of Tears. The Indians were moved from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River – specifically, to a designated Indian Territory (roughly, present-day Oklahoma).

Some went freely, others fought to try and hold onto their ancestral homes but between 1800 and 1900, the American Indians lost more than half of their population.

Having learnt so much more about this era of American history I now realise that those movies from my youth were just stories. Stories that made movies, that in turn made money for the studios who made them and that entertained my father and many more like him. As for me I have a different view of those Native American Indians and an admiration for their survival.

There is also an element of sadness. It feels a bit like I was duped, that I was naive to believe what Hollywood was selling to me. I loved those films or stories as I guess I should now be referring to them.

Also looking back on my childhood history lessons, I realise, they were focused upon English and European history. I even have a History A’level but at no point did we ever follow American history so in that sense how was I to know that ” the West was never in fact won!” but stolen from those who had lived there for many generations?

I wonder what happened to Sacagawea?

LikeLike

If you look her up on Wikipedia there are two alternative suggestions of what happened to her. It makes interesting reading and also includes the fact that Clark adopted two of her children.

LikeLike