When we were planning our trip to America, in addition to spending time travelling from coast to coast and exploring the Eastern seaboard, I wanted to extend my social historical knowledge and learn more about:

The Demise of the Native American Indians

The Slave Trade

My previous posts “Our Navajo Spirit Tour Guide” and “The Western Movies Lied to Me” outline my new knowledge of the first sector. I still have more to learn and have two books to read on my return to the UK which may well spur me into delving even deeper into this subject.

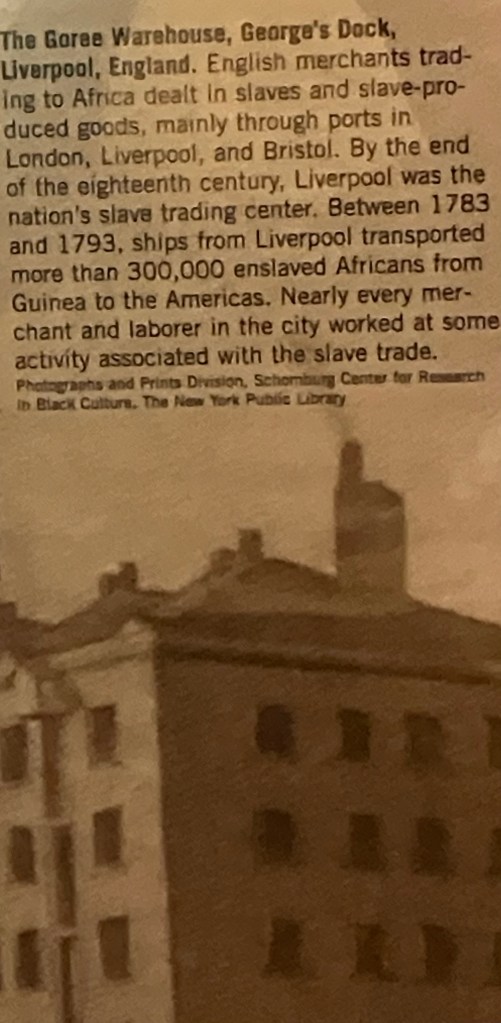

Back in 2019 we had ventured to the North West of England on a short road trip and whilst travelling we had stayed in Liverpool. Here I spent a considerable amount of time one day at The International Slavery Museum based right on the waterfront at Liverpool’s Albert Dock, at the centre of a World Heritage site and only yards away from the dry docks where 18th century slave trading ships were repaired and fitted out.

I had worked in Liverpool in the early 90’s before this museum ever existed and never realised it was a major slavery port and that its ships and merchants dominated the transatlantic slave trade in the second half of the 18th century. The city’s wealth was derived from this sickening trade and it laid the foundations for the port’s future growth.

From about 1500 to about 1865, ships from Liverpool carried about 1.5 million enslaved Africans across on approximately 5000 voyages, the vast majority going to the Caribbean. Around 300 voyages were made to North America – to the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland and it was this I wanted to explore whilst we were here in the USA.

As part of our travels up the East Coast of America we stopped at Hilton Head to take part in a Gullah Heritage Trail Tour. The Gullah/Geechee people of today are descendants of enslaved Africans from several tribal groups of west and central Africa forced to work on the plantations of coastal North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Hilton Head was separated from the mainland by many waterways which made travel off of the islands difficult and rare. The slaves who worked this land, therefore, were cut off from once they had arrived.

It wasn’t until 1956 that a bridge was built that allowed cars to travel across these waterways.

We also visited the Magnolia Plantation in Charleston. This is one of the country’s oldest plantations dating back to 1676. Thomas and Anne Drayton built a house here and owned the rice plantation for the next 15 generations utilising slave labour to build a network of irrigation dams and dikes.

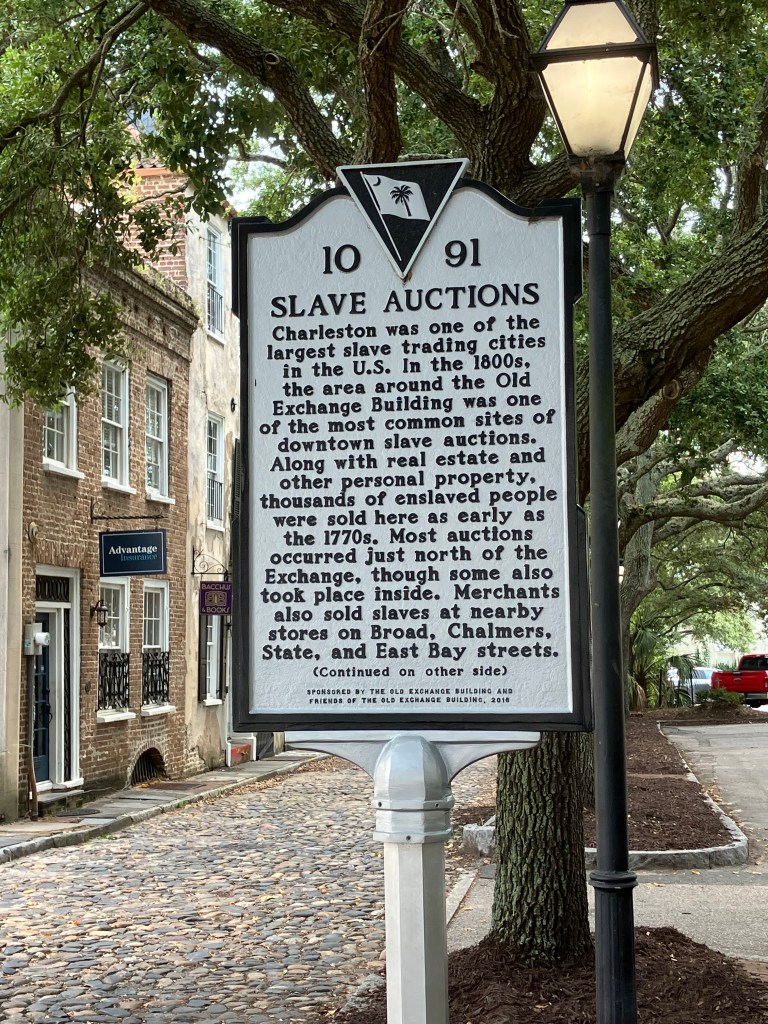

The Old Slave Mart Museum is also in Charleston and covers an important part of Charleston history. This is one of the few remaining buildings once used for securing slave labour. It was constructed in 1859 and once formed part of a much larger slave market taking up an enclosed space between two major streets. It was established by a local sheriff after a ban on public slave auctions and operated until 1865 when it was closed down by the Union forces when they occupied the city.

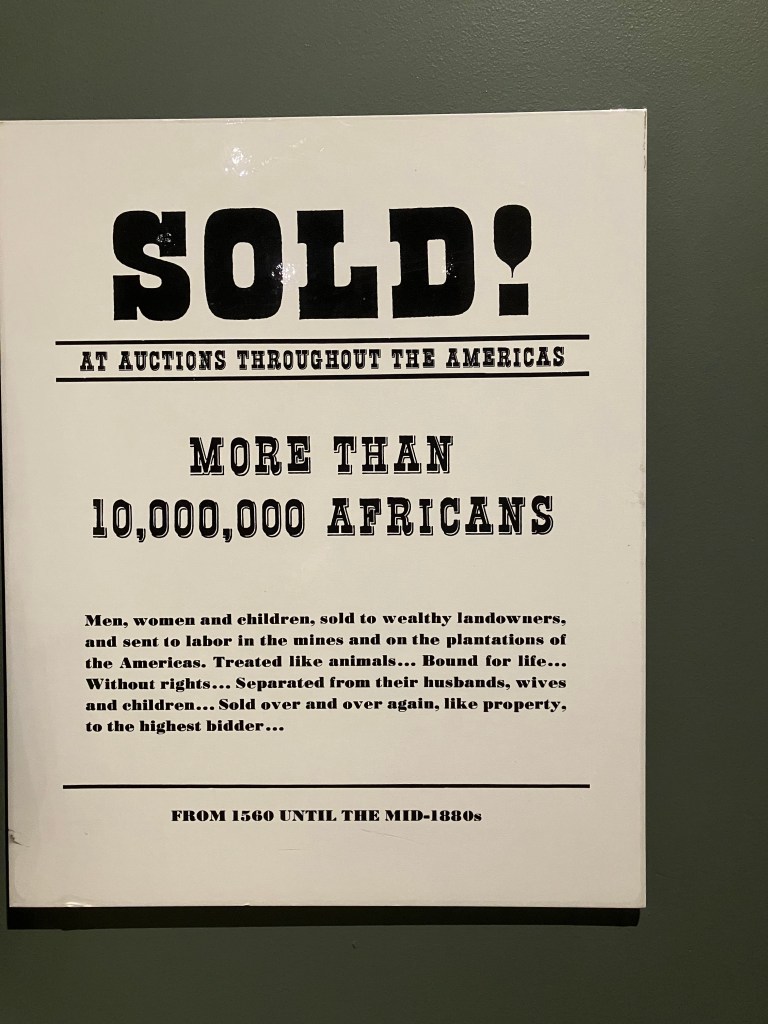

Finally we visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC which devotes a whole floor to the slave trade ensuring that all visitors can be educated on this part of American history.

I still feel that people, particularly those in the middle to higher classes of our society here in England, fail to even try to understand how these people felt or to accept our responsibility as a kingdom for it’s existence. Maybe this story will help you, the reader, to understand…..

” My name is Sam.

This isn’t my real name but the name I have now been given here in this New World.

I am originally from West Africa. It was a wonderful place full of sunshine and laughter.

I am in my mid twenties and I lived a happy life with my wife. She was expecting our first child. We had a home together in the village, that provided shelter from the blazing sun and the yearly rains that fall.

My father taught me how to propagate rice. Food was plentiful and I enjoyed the camaraderie that I shared with my fellow peers. Young men and women that I had known all my life. The traditions and cultures of my ancestors were passed down through the generations. Life was good.

One day whilst I was busy working on our land, my life as I knew it was torn apart. I’d heard tales from other tribes of the marauding English merchants who were capturing local tribespeople and taking them away in chains but not for one moment did I believe they would venture this far inland and arrive at our village.

With the onset of gun shots I immediately ran back towards the village intent on finding my wife and escaping somehow into the surrounding bush. I tore across the rice fields, my feet treading without thought on the crops I have nurtured and grown. Smoke started to rise from the village and my heart was beating fast within my body as I ran faster and harder.

The screams of the women and children can be heard as I approach the outskirts of the village. I have no form of defence and then I see them, the white enemy has arrived. They use their weapons to force the villagers to their knees in the centre of the huts. My wife is crying and clutching at her pregnant belly looking all around for me. I run towards her but before I can reach her, to protect her, something hits the back of my head and I crash to the floor.

When my eyes reopen I am on the ground, it is nearly daylight. My ankles are chained together along with my wrists and I can barely move. My head is sore and I can feel the dried blood coagulated where I was struck. There is no sign of the women and children, only the male villagers remain.

Many, like myself, are nursing injuries brought about while defending their homes and families. As dawn breaks so I am forced to my feet and more chains are used to bind us all together in one long snaking line of humanity.

Leaving behind my home, my village and my way of life we are forced to march from sunrise to sunset for many days. A share of water is distributed two or three times a day. Food maybe once a day and even then it is nothing I recognise, no taste or flavour but I know I have to survive for no other reason than to have the strength to find my wife.

Days melt into one another, my feet are sore and wounded. Older less fit members of the group struggle to stay with the pace. The men who have taken us have no feelings. Those who collapse on the journey are left to die with no water and no food. I estimate that about a third of those who set out from the village are no longer with us. I knew them all, elders who I was brought up to admire, who shared stories of our heritage but there is nothing we can do but move on. Eventually we arrive in a bustling town, large boats, bigger than anything I have seen, are moored to the quayside.

These men who have captured us speak their own tongue and we cannot understand their commands but they make them known through their actions. Pushing and shoving us into a stone building. There are many others already inside and as the door is shut and locked behind us we all want to sit down on the dirty floor and rest, but there is very little room. Some of those already inside look ill and it is hard to avoid staring at them. Everyone is quiet but I try to converse and at first no one answers me, but eventually someone responds.

He understands my tribal language and begins to explain that some of them have been there for many days and nights even weeks. Food and water are scarce.

He explains that the boats arrived over the last few days and the cargo from within has been off loaded. He has heard that we are to be loaded onto the boats tomorrow.

I try and explain about my wife and tell him I cannot go on the ship, I cannot leave this land, my home and my family.

He laughs and asks me who I think is in charge. We have no choice he says.

“Do you want to die” he asks me? I consider this question for a few moments before nodding my head in refusal. “Then do as you are told” he says to me.

Dawn breaks the following morning and with no food and only very little water since our arrival I can feel my body weakening but I must remain strong.

As predicted we are led out of the gate and onto a ship. We are taken down into the depths where it is dark and damp. More and more tribesmen from other villages are brought down. We are packed together below deck and secured by leg irons. The space is so cramped we have to crouch or lie down. The man I had spoken to the previous day is close to me.

“There must have been more stone buildings we could not see” he whispers “there are too many to fit!’

Eventually the door is closed and we are left here not knowing our fate. I try to rest, to close my eyes and sleep.

When I awake I can feel the boat moving from side to side and back and forth and I realise we have left and are now at sea. My country is now far behind me, once again I wonder what has become of my wife. I must find her and to do that I must remain strong. The air down here is foul and putrid. Men are being sick as a result of the constant rocking and the heat is oppressive.

The journey is tortuous but a routine is soon established by our captors. It seems in good weather, when the sun is shining and the boat is steady we are brought on deck midmorning and forced to exercise. We are fed twice a day and those refusing to eat are force-fed. The food is unfamiliar and tasteless but without it I know my strength will weaken and I must stay alive. Those who die are thrown overboard.

It is evident also that we are not alone as when we go on deck we can see two other ships, in close proximity, heading with us across this great expanse of water.

As our journey progresses some of the men become sick. I try to avoid them and focus solely upon myself and my need to remain alive. Others make attempts to escape often during our time above board. Their punishment when unsuccessful is not worth the act. They are tied to wooden posts and we are all forced to watch as they are whipped and then often thrown overboard!

The actions of these men also result in daily inspections of our quarters below deck by the crew and even minor acts of resistance are punished severely.

Some of my fellow Africans cannot cope with this imprisonment and throw themselves into the sea wishing for death over this existence.

Time passes slowly and each day seems to blend into the next until one day there is great excitement above deck and it is not long after this that the ship finally stops. There is a loud noise as if something heavy is being dislodged from the core of the boat and then suddenly the light streams in from above and we are being marched up onto the deck and off the ship. About 50% of the men who came from my village are now dead. I feel lucky to be still alive”.

Sam’s story continues in my next post …………………………