On our adventures in Antwerp we visited a fantastic museum The Red Star Line Museum.

You enter through the door expecting to learn about The Red Star Line which was a group of ships that transported migrants to North America but you leave with so much more knowledge, understanding and empathy for migrants as a whole.

As I mentioned in my previous Antwerp post this specialist museum outlines the story of immigration. Migration is a timeless story. For centuries people have gone in search of a better life elsewhere.

It begins with the true stories of twenty individuals. Each of these people have left their homeland during a period of massive migration. It begins with the dispersion of modern man back in 60,000 to 40,000 BC who left Africa, spreading out across the globe, creating new civilisations and cultures. Within these stories is the story of Irving Berlin, who crossed the ocean to the United States as a child aboard The Red Star Line. The Museum makes it clear that the story of the Red Star Line is just one example.

In the 19th century new waves of migration culminated in the flows of refugees and the forced deportations of entire populations during the two World Wars in the 20th century. Travel has become easier than ever, due to globalisation, modern transport and communication and so through the lives of these people you are brought right up to date with the modern day immigration crisis. One of these twenty people was Kajal Roy and you can read his story below.

Once you get into the museum proper you are introduced to The Red Star Line and you follow the path of the emigrants from leaving their country of origin, through their long journey and temporary stay in Antwerp, to the ocean crossing and their arrival in America or Canada. All of the stories are based upon facts.

Facts that have been gathered from people who maybe crossed the ocean at a very young age or stories told by grandparents and parents of their voyage across the sea. The museum continues constantly gathering this information and they provide research facilities for people who want to search for their relatives who they believe migrated.

I’ve included a couple of the narratives from the museum which enlighten us further on how arduous the journey was.

The Red Star Line was founded in 1871 by Peter Wright & Sons, a company of Philadelphia based shipbrokers and was called the International Navigation Company. They dealt in oil exports and thus the intention was to send their products from USA to Europe and then on the return route, as a way to assuage some cost, they would sell tickets in order to ferry migrants from Europe to USA.

Not so very different from today in terms of money being made from people’s desire to find a better life!

Funds were provided to launch this project by The Pennsylvania Railroad Company who could see the benefits to them, given both the cargo and return passengers would need transportation, having arrived in Philadelphia, to other destinations in the US. In taking on this project they built new docks and terminals in the port of Philadelphia as well as a train station, a loading quay and grain silos.

Clement Acton Griscom was appointed President and in 1872 he travelled to Europe in search of a port for his new shipping line. Antwerp was already an important destination for American oil exports and utilising his contacts he set about establishing the city as the main port through which the migrants would travel.

There was a slight glitch in his plans in so much as the USA Government prohibited combined transports of both oil and passengers, thus the Red Star Line never transported oil but purely migrants. The company also started to look at New York and as this was the biggest port on the East Coast of USA, the Belgian Government became interested in the idea and in 1877 granted a 100,000 dollar subsidy to anyone providing a fortnightly, regular connection between Antwerp and New York and as a result on March 12th 1874 the Red Star Line’s first ship the “Cybele” sailed for New York.

Temporarily during the First World War the fleet sailed under the British flag from Liverpool, assisting in the war effort providing hospital ships as well as shipping cargo and emergency aid.

Post the war everything returned to Antwerp.

Tickets for the ships were promoted all over Europe through agents of the shipping line. Often these agents were local bankers, shop or pub owners who earned some additional income on the side. In order to maximise ticket sales the journey was made as easy as possible with package deals developing whereby travellers could purchase their train tickets to Antwerp and hotel accommodation alongside their boat ticket. This all sounds very familiar when you examine our current travel industry.

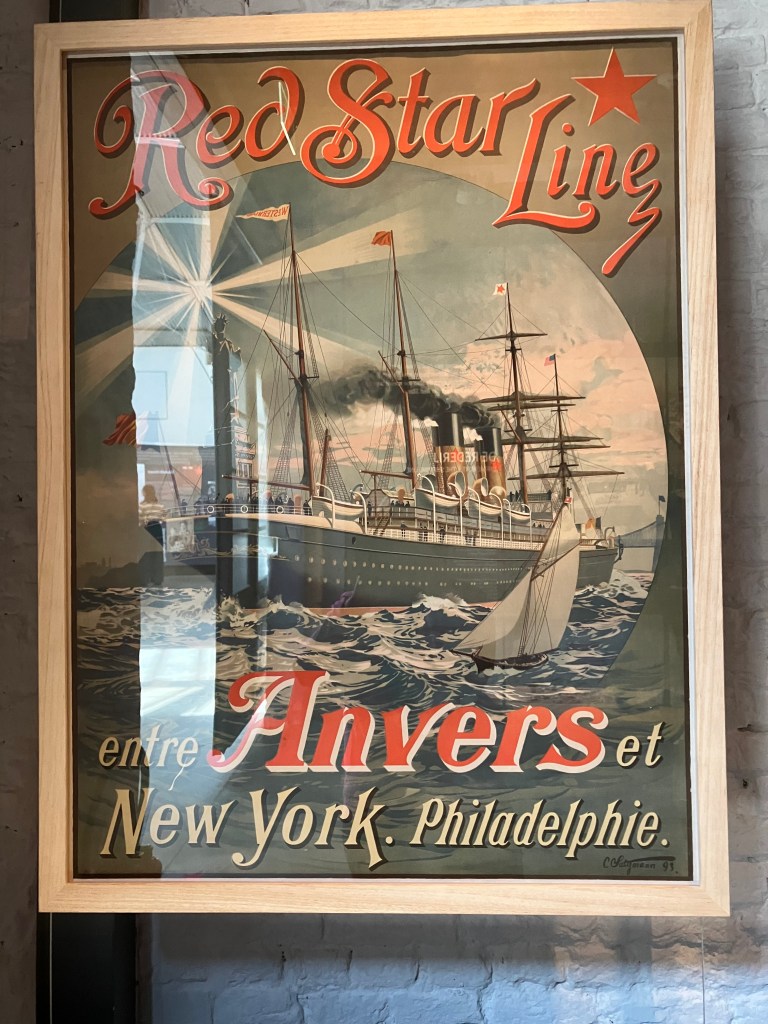

Some of the promotional material developed by the shipping line is on display in the museum. Cost of tickets varied over the years and often also upon the season. Children under 10-12 years of age went half price.

In 1902 an adult ticket in third class would have cost 162.50 Belgian Francs or 31 American Dollars equivalent to about 1000 Euros today. Over a third of the tickets were paid for by family members or acquaintances already in America who when writing home would highlight the advantages of the journey and what America had to offer. Again similarities can be brought in terms of families established in the UK writing emails or sending photos home of the wonderful life they have made for themselves here and encouraging others to follow.

The train journey was the first step. The migrants needed to travel to Antwerp in order to catch the boat. They crossed via the Austrian, German and Belgian borders or travelled internally from Leipzig.

Everyone was checked at the borders and needed a passport. Those without passports would cross illegally by avoiding roads and crossing via open fields. This sounds very like the path followed by those crossing into America today from South and Central America. Especially since smugglers who knew the routes well helped them to cross for a fee and Russian border patrol officers could be bribed.

At Myslovitz on the German border the migrants would be subjected to a first medical examination and their baggage would be disinfected. This was as a result of a cholera epidemic in Hamburg. At the checkpoint here there was a waiting room with a canteen, although food was minimal, but no beds.

Those travelling via Leipzig would travel on trains in separate carriages to all other passengers.

As of the 1890’s those arriving at the Belgian border had to show their ticket and prove they had enough money to cover their stay in Belgium.

On arrival in Antwerp the migrants were spread throughout the city and were very noticeable because of their different mode of dress, with sheepskin coats, colourful headscarves and high boots. In 1913 during a typical week 4000 migrants passed through the city. The migrants fuelled quite a debate amongst local people. Not that different to what we see today!

From 1905 onwards they all disembarked at Antwerp Central station and from 1908-1914 Belgian doctors examined the migrants in the station for infectious diseases. It was important for the shipping line to check that those hoping to travel met with the immigration legislation in place in the USA. If they were turned back on arrival in America then the shipping line had to meet the cost of their return journey.

After the war the Red Star Line built it’s own shower block at the port in Antwerp to further hasten the disinfection and medical checks of the migrants.

Once aboard the ship your comfort was dictated by the class of your ticket. Most migrants lived between decks, in steerage. This was below the main deck but above the cargo hold. Passengers slept on straw mattresses in narrow bunk beds and also ate in the same space. They were required to bring their own bed linen and cutlery. The stories of those who made these voyages make interesting reading within the museum.

On arrival in America all passengers had to meet with the USA immigration requirements. For example you had to be able to support yourself financially. There were restrictions on the disabled, those with a criminal record, pregnant ladies travelling alone, anyone found to have a contagious disease etc.

In first and second class, provided you did not show any signs of sickness, you were allowed to disembark straight away.

All third class passengers, however, had to go through Ellis Island in order to complete administration and medical checks. If you failed on any point you were returned home. From 1925 these immigration formalities were transferred to the European point of departure and thus to Antwerp.

I read a biography at the museum about a family of five; Mum, Dad, two boys and a girl. The girl was only five years old but when she arrived at Ellis Island she was given an intelligence test, as was normal for all and she failed. The Mum and Dad were then faced with the dilemma of whether they all returned to Europe or she went back alone. The Dad went back with her, settled her in a home for what we would these days call “special needs” children and left her there before returning to his family in America!

The museum really proves that migration is not a modern day issue but one that has been around for years. We are more aware of it in modern society because we have newspapers, television and radio but interestingly the difficulties of the migrants are very similar, they are fleeing poverty, racism or war.

I’m looking forward to my next adventure where as part of this journey I will be visiting Philadelphia and more importantly Ellis Island and seeing the other end of the migrant journey.

NB:

This is my second post about Antwerp. It is definitely a city we would return to, why not have a read of my first post? We are currently touring Western Europe, why not join us on our journey and catch up with where we have already visited?